FROM ENGINEER TO DATA SCIENTIST

When moving roles from Software Developer to Data Scientist, the hardest part of the transition for me was the mindset. I was equipped with the technical skills for working with data but found myself without a clear path to navigate a problem space.

I was used to being told a product spec and working on features to be fed into a product release cycle, there is a very well trodden path when it comes to Software Development and I knew it well. As far as I’m aware the process for Data Science is not so well established as even the definition of the role varies so hugely between different companies.

I joined my company’s Data Science team when it was first formed. The team was comprised of people with an eclectic mix of backgrounds, each person having deep knowledge of their area of expertise. However, while some had a background in research, none had worked commercially as a Data Scientist before. This type of team was new to the company as well, it took us all a while to find our feet. In a company full of Software Developers, we were at first treated as if that were our role (which for most of us it previously had been), with similar expectations, and so we attempted to follow similar workflows. This did not work.

During our first year or so the team split into sub-teams for different projects, each working in their own way to provide solutions to business problems. Project workflows varied hugely depending on who was leading the team and during our morning stand-up it was hard to keep track of the progress of each sub-team. It was tricky for other team members to assess whether the end was in sight for a piece of work. It must have been a nightmare for stakeholders trying to keep track.

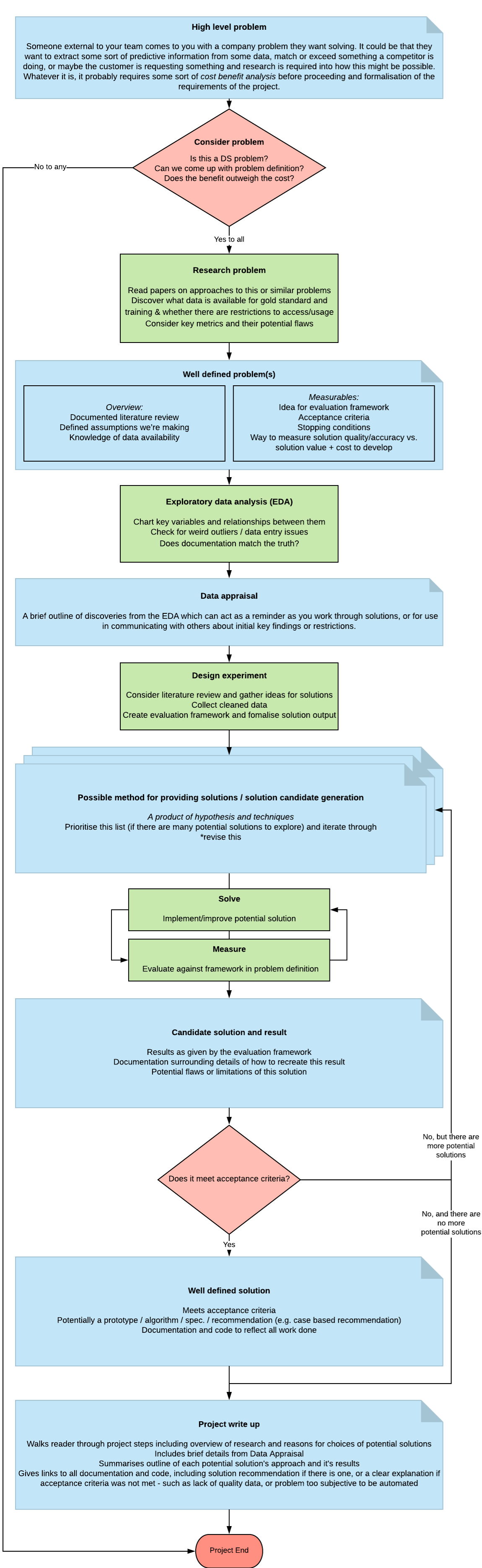

A year or so after it’s formation, the team took time out to work together and feedback to one another on what worked, what didn’t, and how some people (who had experience in either research or leading a tech team) might go about structuring a project or piece of work in a previous role. We did our best to formalise these ideas and sketch an outline of how a research project should go. What follows is my interpretation, somewhat embellished from other research I’ve compiled from online resources. It helps me structure my approach, know where I am in a process, and gives me the satisfaction of having a checklist of tasks to tick off so I can feel safe in the knowledge I haven’t missed a vital part of the process.

PROJECT WORKFLOW

📄 High level problem

In a business context the high-level problem rarely comes from some cool thing a Data Scientist just thought up, or some new piece of technology applied in a zany new way. For us ideas and insight into customer needs often came directly from marketing or sales people, or sometimes was collected by product managers. Either way, the first step in solving the problem is to understand the problem. Get clarity on the high-level problem, know where it’s come from, and get a clear set of requirements.

The 📄 emoji in this heading signals that you should write this down. Make a shared doc.

❔ Consider problem

Before delving too deep and investing a lot of time in the project there’s a few things to get clarity on. No. 1: Is this really a Data Science problem? Could it be solved by a simple new feature in the software or does it really require some deeper analysis, modelling, and research. In some cases problems can be solved by Engineers by use of third party libraries (this will come up in the cost-benefit analysis). Only when such other options have been ruled out, and the decision is clear that the benefits of solving this problem are worth the costs, will you start to research the problem space to come up with a clearly defined problem spec.

📝 Research problem

It’s easy to get carried away and jump right in. You come up with a smart solution and want to try it out immediately. This might be enjoyable, but it is not the most efficient use of your time. It’s likely that many have come before you in trying to solve your problem, or something relatively similar.

Read papers on approaches to this or similar problems, often they can point you in the direction of some good data sources to use as gold standard for tests (otherwise you will need to compile this for yourself). You will want to find out where you can get your training data from and whether there are restrictions for usage or access.

As you assemble a pool of promising solutions you should consider the potential quality or accuracy of each approach against the cost of building it into a business application. For example using a heavily complex solution such as layers of neural networks or a Spark cluster, that few know how to update or maintain, or there isn’t available hardware for, might not be worth the increased accuracy vs. a simpler solution. If the cost of the complex solution is ruled out, you can drop any ideas to do with that now without wasting time exploring something that might be technically feasible, but commercially invalid.

📄 Well defined problem

The output of your research should include a literature review, taking heed from the mistakes of others and inspiration from their ideas. By this point you should have really evaluated what it is you are trying to do, and have a solid understanding of how the results of your work will be used. You should have access to and be ready to explore the data you have available. Assess the assumptions you will be making so you can have a level of awareness if they fail to hold up.

A well defined problem will include some idea of how you will structure your scientific evaluation system. What variables will you use to assess and compare the quality of a solution? How good is good enough? What if you fail to achieve this, at what point can you prove this problem cannot be solved? Try to draw up a set of stopping conditions.

Again, the 📄 emoji signals that you should have a document (or set of documents) for this.

📝 Exploratory data analysis (EDA)

Before building any complex models, it’s important to get familiar with the data you will be working with. Look over any documentation and take note if there are gaps or errors in explanation (if it exists at all), attempt to identify key variables and chart relationships between them. This is a good time to check for outliers or data entry issues that might be skewing your data.

📄 Data appraisal

Collate the information from the EDA phase into a shared document that you can refer to in future. It will be a good reminder as you are working your way through potential solutions of any pitfalls that may come from the data, and it can act as something to point to when communicating reasons for choices with stakeholders.

📝 Design experiment

Combine the information you have gathered from the defined problem and data appraisal to set up an experiment workflow. Take into account details from your literature review, decide upon the measurables you are going to put in place to evaluate quality of solutions, the data available, the limitations of maintainability and cost, and compile a list of possible solutions ordered by priority of simplest first to the increasingly complex.

Your workflow should include an evaluation framework, a spec for the measurables that can be fed into this framework so that each solution can be designed to output these and therefore be directly compared to other solutions.

📝 Solve - Measure Cycle

Starting with the simplest solution to get a baseline, work through potential solutions one at a time. This is represented by a cycle because you will evaluate your solutions as you go and continue to tweak them for a time. If, or when, tweaking this particular approach is failing to give much improvement then evaluate the candidate solution and potentially move on to the next plausible approach.

If at any point the solution meets the requirements laid out in the defined problem, or stopping conditions are met, then stop here, you have your result.

Time spent on each solution should be roughly time-boxed, there is usually limited time-resources and you don’t want to become so invested in your first potential solution that you fail to move on to something that might be more appropriate. At the same time you don’t want to give up so quickly that you fail to see the value in a given approach. It’s all about finding the balance.

📄 Candidate solution and result

The result will consist of the measurables that were fed into the evaluation system, and how the solution performed compared to others tested. It will also include specific details about models used, parameters, data used for training. There must be enough information such that it can be replicated if someone else were to come across this information and want to try it. A repo containing the code along with some documentation is ideal.

❔ Does it meet acceptance criteria

The acceptance criteria will have been agreed upon with stakeholders when first defining the project. If the solution is good enough to meet this criteria it is likely that it’s time to stop, write up your results, and move on. Most Data Science projects could go on indefinitely without these constraints, you could go on forever tweaking parameters and trying different approaches, there will always be room for improvement. The acceptance criteria is here to tell us that this is good enough.

If the solution doesn’t meet the acceptance criteria, you can continue on to another potential solution. If you’re out of solutions, it’s time to write up the project and feedback the results.

📄 Well defined solution

A well defined solution will contain the information from the original candidate solution section but will be extended to include some sort of prototype or specification giving a recommendation of how this solution could be built into a product to meet the business needs. It will reconsider the high level problem and how this approach can be used to solve it.

📄 Project write up

This is a summary of all of the preceding stages. It walks the reader through the project’s steps, including an overview of the research done, and reasons for choices of potential solutions. It includes brief details from Data Appraisal, and summarises and outline of each potential solution’s approach. It will cover trialed results without getting too bogged down in numbers. The write up should provide links to all documentation and code, including a solution recommendation if there is one, or a clear explanation if acceptance criteria was not met - such as lack of quality data, or problem too subjective to be automated. This is storytelling and not scientific.

Congratulations if you made it this far 🏅 And thanks for reading my first post! I’ll be adding new posts soon so please do drop by again.